Information for advice professionals only.

What is private equity?

Private equity is an asset class in which capital is invested in private companies in exchange for equity or ownership. Private companies are not publicly traded or listed on a stock exchange. Public companies can also be acquired by a private investor – in these circumstances, the public company becomes private and is de-listed. The industry currently has a total AUM of $4.11tn. In 2019, the average value of a buyout deal was $487mn.

Private equity capital comes primarily from institutional and accredited investors that either invest directly in companies, or through funds managed by fund managers. In comparison to public equity investments, which trade daily, these are long-term and illiquid. Some of the most active investors are private equity fund of funds managers, pension funds, endowment plans, and family offices. More recently, there has been increasing interest in the asset class from private wealth investors.

Definitions of private equity differ. In its broadest sense, the term can include niche strategies such as venture capital, real estate, infrastructure, and debt transactions - this is what Preqin would refer to as 'private capital.' For the purposes of this lesson, private equity specifically refers to investments made in companies, as opposed to hard assets such as real estate or infrastructure.

Test your knowledge and earn CPD

Take this short, multiple-choice quiz to test your private markets knowledge and earn CPD.

The history of private equity

Having an understanding of the history of private equity, from its early beginnings to the modern day, can help investors appreciate the impact market cycles and changes to legislation can have on the asset class.

Pre-1900s

Investments in private companies can be traced back to the dawn of the Industrial Revolution, when wealthy individuals and families contributed capital to railroads and other industrial companies.

Early 20th century

1901

Widely accepted as the first major buyout transaction, J. Pierpoint Morgan acquired Carnegie Steel Company for $480mn.

1946

Founding of the first two venture capital firms: American Research and Development Corporation (ARDC) and J.H. Whitney & Company.

1955

McLean Industries Inc. purchased Pan-Atlantic Steamship Company and Waterman Steamship Corporation, the first examples of leveraged buyout transactions.

1958

The Small Business Investment Act passed, allowing the licensing of ‘Small Business Investment Companies’ (SBICs) to help the financing and management of small businesses in the US. The act gave venture capitalists access to federal funds which could be leveraged up to a ratio of 4:1 against privately raised investment funds.

Late 20th century

1960s and 1970s

The SBI Act resulted in the establishment of the first common form of private equity fund – a traditional pooled fund structure. Private equity firms could form limited partnerships (LPs) to hold investments, with investment professionals acting as general partners (GPs).

1980s

The first ‘buyout boom’ era, a period characterised by large numbers of leveraged buyouts and hostile takeovers. Buyout activity accelerated due to the availability of high-yield debt financing, also known as ‘junk bonds.’ One of several high-profile disasters, the junk bond crash in 1989 led to restrictions on the industry to prevent riskier practices.

1990s to 2000

Private equity investors began to take a longer-term approach to companies acquired. During this period transactions typically utilised lower leverage levels in response to the excesses of the 1980s. The number of private equity investors also grew significantly, and in the early 1990s the Institutional Limited Partner Association (ILPA) was formed as a trade association for limited partners in private equity.

In the mid-to-late 1990s, venture capital activity grew, the internet rose to prominence and the dotcom bubble expanded. Companies like Amazon, AOL, eBay, Netscape, and Yahoo were all recipients of venture capital financing. This meant that private equity & venture capital firms were severely affected by the NASDAQ crash (2000) and the bursting of the internet bubble. Valuations for start-up technology companies collapsed and those leveraged buyout firms that had invested in telecommunications were also impacted.

21st century

2002

As a result, global economic activity was slow at the turn of the century. The Federal Reserve looked to stimulate the American economy through a series of interest rate reductions.

2003 to 2007

The second ‘buyout boom’ came when low interest rates drove asset owners to private equity in search of yields. Lowered borrowing costs enabled private equity firms to finance larger acquisitions. The number of private equity deals soared and mega deals in excess of $20bn were made by the likes of Kinder Morgan, iHeartmedia, Hilton Worldwide Holdings, and First Data Corporation.

2008

The collapse of Lehman Brothers heralded the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). Activity was depressed during this time as private equity firms had difficulty finding attractive investments and obtaining debt financing.

2011 to now

'The Third Boom’ arrived as financial markets started to recover. 2011 was the first year since the crash where the capital distributed back to asset owners surpassed capital being called up for investment. This was the result of a steep rise in exit activity as asset managers looked to exit the investments that they had held onto during the crisis. This trend accelerated and provided asset owners with huge amounts of liquidity, which in turn led to an unprecedented growth in fundraising from 2013 to present.

The enormous growth post-Global Financial Crisis has largely been driven by investor demand as a result of the high returns achieved by the asset class, with investments outperforming the public markets. This trend has continued in response to increasing global wealth concentration, with a rising class of private wealth investors striving to access the high potential returns on offer.

Today the term private equity is very different to what it was 20 years ago. The traditional pooled fund structure is still widely used and accounts for most of the capital at work in the industry, but managers have evolved their offerings to cater to the changing needs of investors. Many investors are utilising alternative methods of accessing the asset class such as direct investments, co-investments, and separately managed accounts. Meanwhile, some managers are moving away from the traditional commingled fund to more customised offerings and branching into new asset classes and strategies, such as private debt.

Private equity vs. venture capital

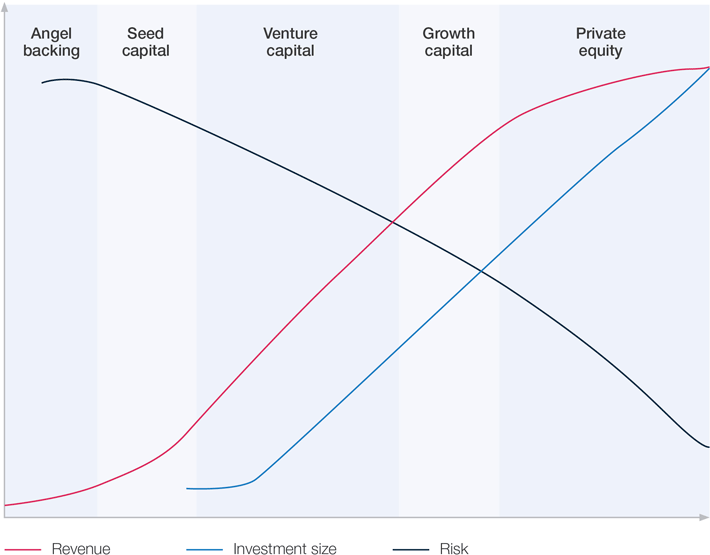

As already outlined, ‘private equity’ as a generic asset class term encompasses a multitude of different investment strategies, including venture capital. However, when used at the investment level there are key differences between private equity and venture capital investments; foremost of which is the maturity of the portfolio companies invested in. Venture capital investments are characterised by providing capital to young, start-up, or early stage businesses that are, or have, the potential to grow quickly.

VC investments are characterised by iterative rounds of financing with additional capital provided as the business scales and return on investment is achieved. Private equity investments are typically in larger, more mature businesses with proven financial record. Further differentiating traits include:

- Risk – VC investments are higher risk than PE, due to the unproven nature of the businesses invested in.

- Ownership stake – VC firms typically acquire minority stakes whereas PE firms acquire controlling stakes.

- Structure – VC firms normally make pure equity investments whereas PE firms use equity and debt.

- Investment amount – PE investments are typically larger than VC investments as they acquire greater ownership stakes and are in more mature businesses.

- Value creation – VC investments rely on company growth and valuation of the business increasing, whereas PE investments rely on both growth and financial engineering including multiple expansion, debt settlement, cash generation, to name a few.

As the industry has grown and firms have broadened their offerings for investors, lines have blurred. Some VC firms have moved into expansion and growth areas, and some firms also provide debt financing (venture debt) to pre-revenue companies. Some traditional PE firms are also moving down the chain, raising dedicated funds focused on early-stage start-up investments.

Private equity investment strategies

There are six key strategies and fund types for private equity investments – buyout, venture capital, growth capital, turnaround, fund of funds, and secondaries.

Buyout

In a buyout investment, the investor often has complete or majority ownership and control of the company. Frequently, investors ‘shake up’ or replace the management teams and are involved in operational decision-making. Buyout represents the largest strategy segment within private equity as measured by assets under management, and as such has a meaningful impact on the aggregated performance of private equity as an asset class.

The investor controls investments in the equities of mature private companies using a combination of equity and debt. Debt is often utilised as it has a lower cost of capital than equity since interest payments reduce corporate tax liability, unlike dividend payments.

Venture capital

Investments made in start-up companies and early-stage businesses that are believed to have significant growth potential. There are different stages of venture capital financing across angel, seed, late stage and expansion, which are reflective of a company’s maturity level. As a company grows, additional financing is provided in the form of ‘rounds’ to facilitate further development.

Growth capital

Growth capital can be seen as part of the venture capital strategy or its own strategy. For this type of strategy, investors take a minority or non-controlling stake in companies they believe will grow. In most circumstances, the investor has a passive approach and retains the same management team to oversee operations. The companies invested in are often relatively mature compared to venture capital, but less mature than the companies targeted in buyouts. The focus is more on market expansion as opposed to cost cutting or financial engineering. Typically, lower levels of leverage are used in growth capital than for buyout transactions.

Turnaround

This strategy targets companies with poor performance, or those experiencing trading difficulties. The basic concept is to buy cheap and sell high, with the difference between the depressed price at purchase and improvements at the time of sale creating a return on investment.

Private equity fund of funds

Funds of funds are vehicles raised by managers with a mandate to invest in the funds of other managers. The key value add for the investor is that they need only conduct a diligence process around the manager they have invested with. The fund manager will then proceed to source potential investments, carry out due diligence, and monitor the other managers holding the investors' capital.

However, there are often higher fees and a smaller portion of profits go to the allocator, with less control over the underlying managers selected. This is a good option for allocators with small or inexperienced investment teams who would not be able to carry out the allocation process in-house.

Secondary fund of funds

This is a specialised fund type that looks to purchase other investors’ stakes in private equity funds. These funds will capture a portion of the anticipated growth in value of an investor's fund stake. Depending on when the fund stake is sold, the buyer may not obtain the full value of growth, as a percentage will have already gone to the original investor.

Private equity risk and return

While private equity has often delivered returns at the higher end of the private capital spectrum, it is also one of the riskiest private capital strategies, primarily due to the nature of the assets. The equities of private companies often derive their value from intangibles like brand, customer base, patents, and distribution channels, which are harder to liquidate in times of difficulty than physical assets such as real estate, gold, or oil. These physical assets are tangible, easier to value, and usually hold at least residual value in times of crisis, making them less risky.

Private equity market performance can be analysed in several ways. This includes making comparisons against the public markets, capturing average returns earned by LP portfolios based on the amounts invested, or analysing a fund’s internal rate of return (IRR).

| Fund Type | Return - Median Net IRR | Risk - Standard Deviation of Net IRR | AUM ($bn) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Balanced | 12.0 | 15.2 | 278.7 |

| Buyout | 17.4 | 15.9 | 3978 |

| Early Stage | 15.4 | 26.4 | 797.1 |

| Fund of Funds | 15.8 | 8.8 | 1018.1 |

| Growth | 12.6 | 21.1 | 1381 |

| Secondaries | 18.1 | 12.1 | 496 |

| Turnaround | 19.3 | 38.8 | 26 |

| Venture Capital** | 13.1 | 23.4 | 1911.2 |

The size of the circle represents AUM as of December 2023

** Venture Capital excludes early stage

Private equity risk and return by investment strategy

Buyout

Buyout is the largest strategy segment within private equity as measured by assets under management. Therefore, it has a significant impact on the aggregated performance of the entire asset class. Buyout funds have generated strong and steady returns in recent years, driving much of the cash distribution seen in the private equity industry and contributing to investors’ positive view of the asset class. Smaller buyout funds often post the highest returns, as at purchase they are lower in price and worth significantly more by the time of sale. Larger buyout transactions also present opportunities for strong returns, as companies restructure with the aim of improving operations and finances.

Venture capital

Venture capital has one of the highest potential rates of return, particularly for early-stage investments. However, the success rate of early-stage companies is highly variable, with some experiencing phenomenal growth and others failing altogether. This creates a wide variation in outcomes for investors in the strategy: less than 20% of venture capital investments deliver positive returns. Later-stage venture capital investments carry lower risk as they are further along in their development, but this makes the potential returns lower too.

Growth capital and turnaround

Growth capital and turnaround investments also carry a reasonable amount of risk as they rely on growth or improvements in company performance actually being achieved. The returns for growth investments are not as high as buyout transactions due to the non-controlling stakes often taken, whereas in turnaround investments investors tend to buy low and sell high, therefore reaping higher returns.

Fund of funds and secondaries

Investments in fund of funds and secondaries tend to carry the lowest risk. In secondaries funds, risk is minimised as investors already have an indication of the type of assets held in the fund as opposed to a new fund that has yet to deploy capital. In funds of funds, investments are diversified across multiple strategies which can help provide exposure to a range of sectors, styles and geographies, thus reducing the overall risk. However, additional fees associated with fund of funds can detract from total returns.

Why invest in private equity?

Private equity is a well-established part of many institutional investor portfolios, as it generates higher absolute returns while also improving portfolio diversification.

| Reason | Private equity | Venture capital | Private debt | Real estate | Infrastructure | Natural resources | Hedge funds |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diversification | 68% | 47% | 72% | 64% | 75% | 62% | 63% |

| High risk-adjusted returns | 62% | 45% | 39% | 35% | 30% | 21% | 26% |

| High absolute returns | 57% | 63% | 25% | 15% | 9% | 7% | 34% |

| Low correlation to other asset classes | 20% | 9% | 32% | 36% | 41% | 24% | 39% |

| Inflation hedge | 5% | 2% | 14% | 51% | 54% | 38% | 5% |

| Reliable income stream | 6% | 0% | 58% | 55% | 55% | 10% | 0% |

| Reduce portfolio volatility | 22% | 3% | 42% | 31% | 36% | 10% | 32% |

1. High absolute returns

As in public equities, investors in private equity are subject to market risk, credit risk, and operational risk, but they also carry additional risks due to the illiquidity of underlying assets. The limited regulatory oversight of management and reporting conventions is seen as another investment risk within private equity. As a result, investors expect a higher return for their private equity investments relative to those in publicly traded stocks.

2. Diversification

Exposure to private, unlisted companies provides investors with uncorrelated returns and a greater degree of diversification within their portfolio. For example, a private equity fund may give an investor exposure to a range of sectors or types of companies which are underrepresented in public markets.

3. High risk-adjusted returns

Risk-adjusted returns are measured by comparing the level of risk involved in the investment and its subsequent return. The volatility of returns associated with private equity tends to be lower than that of publicly traded equities as the assets are not marked to market daily. A smoother return profile can help private wealth investors stay the course and not make irrational decisions based on short term market movements.

Test your knowledge and earn CPD

Take this short, multiple-choice quiz to test your private markets knowledge and earn CPD.

Information current as at June 2024. This content was produced by Preqin Ltd and adapted with permission by BT Financial Group. This document may contain material provided by third parties derived from sources believed to be accurate at its issue date. While such material is published with necessary permission, the Westpac Group and Preqin accept no responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of, nor does it endorse any such third party material. To the maximum extent permitted by law, we intend by this notice to exclude liability for this third party material. The content is based on the best data readily available at the time of creation, however the accuracy, completeness or timeliness of such data is not guaranteed. Content may include general financial information and examples; however, these are for illustrative purposes only, and may not be applicable to your personal circumstances or needs. The content does not constitute financial or investment advice and the content hereunder should not be considered as a substitute for professional advice. Any projections or forecasts presented may involve risk and uncertainty, and actual results may differ materially from those presented, projected or forecast. Past performance is not a reliable indicator of future performance. This communication has been prepared for use by financial planning professionals only. Except as permitted by the copyright law applicable to you, you may not reproduce or communicate any of the content on this website, including files downloadable from this website, without the permission of the copyright owner.