Key Points

- Elevated Inflation, Geo-political instability and Central Bank rate hikes have led to volatility in equity markets globally.

- Historically, major geopolitical events have been minor near term bumps in the road for equity markets.

- When looking at equity market valuations, interest rates are only one variable to consider - corporate earnings also play a large factor.

The start of 2022 has been a tumultuous ride for equity markets. Investors have navigated an array of fresh and existing uncertainties, including the Omicron variant, inflation, the prospect of interest rate hikes and most recently, war in Ukraine.

As a result, volatility has been elevated over the start of 2022. This is perhaps best captured by the CBOE VIX volatility index, which has averaged a level of 26.1 over the year to date to 15 March, compared to 19.7 over 2021. The VIX index represents the expected volatility over the coming 30 days for the S&P500. However, the swings in the market over the start of the year have largely landed in the red; the S&P 500 index is 10.6% lower over the year to date and the Euro Stoxx 50 is down 13.0%. Domestically, we have experienced a more modest decline in valuations, the ASX 200 closed down 4.7% over the year to 15 March. The slide in market performance comes despite a generally strong reporting season over the start of the year, as many companies delivered earnings above market expectations.

Although uncertainty surrounding COVID-19 has dominated markets over the past two years, the conflict in Ukraine and concerns of rising interest rates, including tighter central bank policy, have overtaken as the key drivers of equity market sentiment.

This begs the questions, why are these factors effecting equity market performance and should we expect stock markets to grind lower as these factors evolve?

Geopolitical events

The war in Ukraine is a humanitarian disaster of immense scale, however, the conflict also has considerable implications for financial markets. As we have observed, equity prices across the globe have fallen sharply since Russia invaded and have moved around violently since that time, alongside changes in market sentiment.

One of the direct transmission channels driving market sentiment has been a surge in commodities prices resulting from the conflict. Russia is the world’s third largest producer of crude oil and petroleum products and the largest producer of natural gas. While together, Russia and Ukraine account for a large share of global production of wheat, base metals and precious metals.

Concerns around ongoing supply of commodities produced by Russia and Ukraine have driven a surge in commodities prices – both for commodities in which Russia and Ukraine account for a large share of production and commodities which may be substitute impacted resources, such as coal. Higher commodity prices are a headwind for growth, pressuring corporate margins and consumer purchasing power, as well as dampening confidence and therefore have negative implications for market sentiment.

However, history tells us that the impact of geopolitical conflict on equity returns is generally short lived and that stock markets tend to rebound quickly. However, much depends on the scale, duration, and location of the conflict.

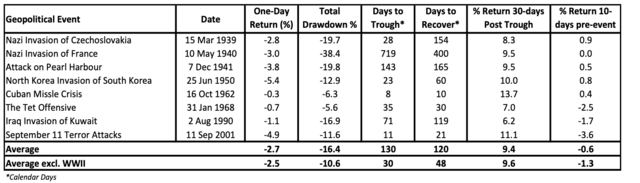

This is apparent examining eight major geopolitical events which have occurred since 1939. On average, each event has wiped 16.4% off the US S&P 500 share market. Importantly, it has taken an average of 120 calendar days for the index to unwind these losses. This is shortened to 48 days when removing prolonged conflicts during World War II. Encouragingly, in the aftermath of major geopolitical events the S&P 500 has jumped an average of 9.4% in the 30-days following the market trough.

While observing history is a useful exercise, it is also important to acknowledge that, of course, these events do not occur in a vacuum. The macroeconomic backdrop, and monetary and fiscal policy are also important drivers of equity markets. In addition, equity markets have undergone major changes over the period examined, including the rise of algorithmic trading, changing composition and broadening derivatives markets.

It is too early to tell whether markets have bottomed out as a result of the Ukraine war, and much will depend on the duration and scale of the conflict. This is especially true when considering the importance of Russia and Ukraine in global commodities trade. A prolonged or more severe conflict would likely keep commodities prices higher for longer via more significant disruptions to supply, denting global growth. Indeed, the risks around stagflation have grown since the invasion of Ukraine began. Further, if Russia were to escalate the conflict beyond Ukraine, there could be much broader implications for share markets and beyond.

So far, the Australian share market’s reaction to the conflict has broadly mirrored that of the US. However, the S&P/ASX 200 index has outperformed a number of major share market indices. This partly reflects compositional factors – the resources sector accounts for a sizeable share of the index and has been boosted by the jump in commodity prices. Australia is also relatively more sheltered against the impacts of the war due to its geographical location and limited direct trading ties with Russia and Ukraine, which collectively account for less than 1% of our exports.

Rising Inflation and Interest Rate Expectations

While the longer-term implications of the Ukraine war on stock market valuations is uncertain, the reality of rising interest rates is sure to continue to drive market sentiment over 2022, even after the effects of the war have abated.

Inflation picked up markedly across the global economy over 2021 and into 2022. Supply-chain disruptions were prevalent, and remain so, as rebounding demand intersected with constrained supply. Labour markets also tightened considerably, and wage pressures are building to varying degrees across the globe.

The conflict in Ukraine has added another layer of uncertainty, driving higher inflation through surging commodities prices and further supply difficulties, while constraining global growth at a time when central banks are under pressure to rein in inflation.

As a result, expectations of the likely timing and path of global interest rate rises have been brought forward, and Australia is no exception.

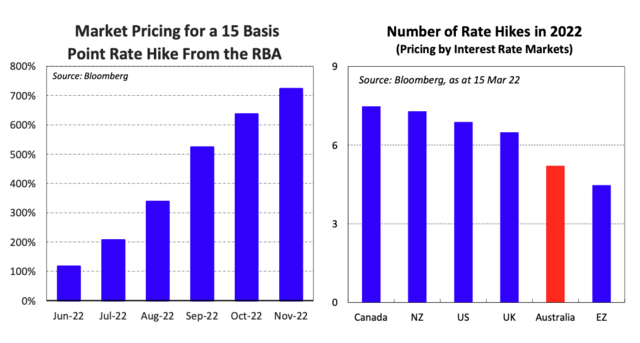

Although Australia has experienced relatively weaker inflation compared to its counterparts in the US, UK, NZ and Canada, the Reserve Bank (RBA) Governor recently conceded that it is plausible for the cash rate to increase in 2022. This is a far cry from only four months earlier, when the Governor reiterated that their central case scenario was that interest rates wouldn’t increase until 2024. However, the Australian economy has performed much better than the RBA expected over the pandemic. Inflation has now entered the top half of the RBA’s target band for the first time in more than seven years and is expected to remain at or above that level over 2022 and beyond.

Markets have persistently challenged the RBA’s guidance on rate hikes – anticipating an earlier move – over concerns inflation would run hotter than the central bank expected. Rate hike expectations have been pared back slightly following the conflict in Ukraine, however, markets are still pricing an aggressive interest rate profile from the RBA. Indeed, markets are fully pricing five rate hikes from the RBA this year, which would take the cash rate to 1.25% by the end of 2022.

Investment Implications

Equity market performance has suffered, partly due to expectations of a faster tightening of monetary policy. Indeed, in January, the ASX 200 index shed 6.4% largely driven by concerns of interest rate hikes in the US. This is the largest monthly fall in the ASX 200 index since March 2020, following the outbreak of COVID-19.

The question which remains is why are growing inflation expectations paring equity valuations? And can we expect a prolonged period of equity market underperformance, as we approach an interest rate tightening cycle for the first time in more than a decade?

‘All other things being equal’, higher interest rates will have a negative effect on equity valuations. A typical way to value a company is the sum of its future cash flows, discounted to today by a discount rate. A higher rate means a lower value.

Unfortunately, reality does not adhere to neat valuation models. A company has many factors that determine valuation, including the timing of those cash flows, the ability to grow earnings and investors continually evolving perception of risk. Higher interest rates alone do not necessarily mean lower equity returns.

Adam Dearing

Portfolio Manager BT Investments

Jameson Coombs

Associate Economist - BT Economics

Economic update - Home Loan Clampdown on the Cards

This document has been created by Westpac Financial Services Limited (ABN 20 000 241 127, AFSL 233716). It provides an overview or summary only and it should not be considered a comprehensive statement on any matter or relied upon as such. This information has been prepared without taking account of your objectives, financial situation or needs. Because of this, you should, before acting on this information, consider its appropriateness, having regard to your objectives, financial situation and needs. Projections given above are predicative in character. Whilst every effort has been taken to ensure that the assumptions on which the projections are based are reasonable, the projections may be based on incorrect assumptions or may not consider known or unknown risks and uncertainties. The results ultimately achieved may differ materially from these projections. This document may contain material provided by third parties derived from sources believed to be accurate at its issue date. While such material is published with necessary permission, Westpac Financial Services Limited does not accept any responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of or endorses any such material. Except where contrary to law, Westpac Financial Services Limited intends by this notice to exclude liability for this material. Information current as at 10 December 2021. © Westpac Financial Services Limited 2021.