If you have ordered anything online recently, you can probably attest to the impact of supply-chain disruptions. Delays in deliveries have become standard, alongside skyrocketing shipping costs for importers and exporters. The lengthy delays mean some businesses are facing material shortages.

So, what exactly is underpinning the bottlenecks?

Well, as much as I like a succinct answer, there isn’t just one cause.

Much of the problem stems from COVID-19-related developments. Transport bottlenecks emerged last year because of a sharp increase in global demand for goods. Due to lockdowns, the demand for goods jumped sharply while services consumption plummeted. But at the same time, factories were hit with constraints on their operations.

As 2020 wore on, a global shortage of shipping containers emerged, as well as a mismatch in the location of containers, which were often full in one direction and empty in the other. This shortage was exacerbated by congestion at some ports.

On top of that, global supply chains have also been hit by diplomatic tensions, power shortages in China and extreme weather. Oh, and the Suez Canal was also blocked for six days in March this year.

All that is to say, the bottlenecks in supply chains are a complex, multifaceted problem and they are unlikely to be resolved in the short term.

Wide-reaching ripples

The disruptions have snowballed over the past year. Purchasing managers’ index surveys, conducted by Markit in 44 countries, provide one measure of bottlenecks. Through 2021, the survey suggests supplier delivery times have consistently deteriorated across the globe.

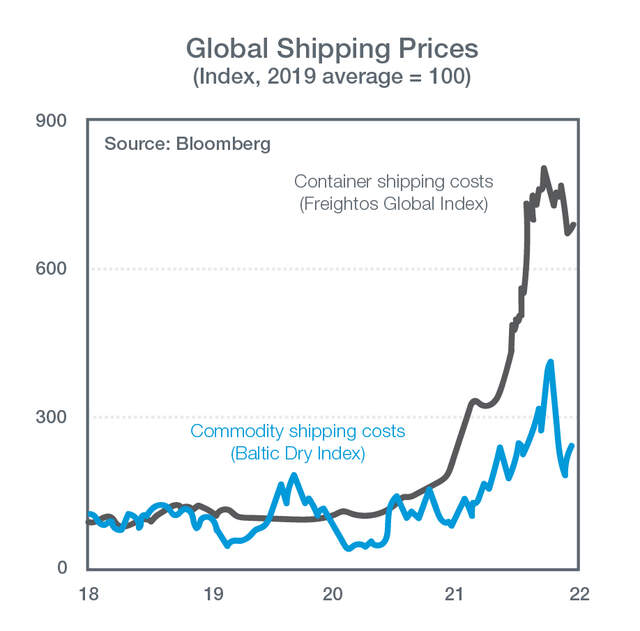

Meanwhile, container shipping costs have surged over 600% since the start of 2020, according to the Freightos Baltic Index – a benchmark metric based on freight rates in 12 important maritime lanes. Costs have moderated somewhat in recent months. Encouragingly, the Baltic Dry index – a proxy for dry bulk shipping costs – has fallen more significantly, although also remains elevated relative to pre-COVID levels.

An April survey conducted by the Australian Bureau of Statistics found around 30% of Australian businesses had been impacted by supply-chain problems. However, given these issues have continued to persist throughout the year, this figure is likely higher now.

In light of the developments over the past 18 months, many businesses have reassessed the resilience of their supply chains, pushing some businesses to diversify their supply network to avoid dependency on a particular country.

Importantly for Australian manufacturers, there is a push to scale up domestic production capabilities for critical products. The government has noted medicine, personal protective equipment and fertilisers as points of focus.

Another consequence of supply disruptions is that energy-related commodity prices have increased significantly since the middle of the year. Energy price have been boosted by strong demand for goods alongside the global economic recovery.

Relief is coming… eventually

The immediate question is, how much longer will these disruptions persist?

Unfortunately, it will take some time for these bottlenecks to be worked out. Our customer liaison suggests that disruptions will persist in some form for at least another 12 months.

On the upside, the move to relax COVID-19 restrictions around the world (notwithstanding recent setbacks in some countries) will see a rebalancing in consumption back towards services and away from goods. The Reserve Bank (RBA) Governor Lowe has recently stated he expects this shift may help disruptions begin to ease over the next six months. However, Lowe made these remarks before the emergence of Omicron. Omicron could prolong the supply-chain disruptions for longer.

Inflationary pressures are swelling

The disruptions to supply chains, alongside strong goods demand and rising energy prices, have pushed producer price inflation to its highest level in many years in a number of economies. However, the extent to which this has been passed onto consumers varies.

This has put inflation front and centre of policymaking agenda. In fact, US President Biden has said that reversing inflation is a top priority, as sharp increases in prices weigh on his approval ratings. In the US annual producer price inflation surged to 12.5% in the year to October. Personal consumption expenditure (the Federal Reserve’s target measure of consumer prices) hit 5.0% in October, the fastest rate since the early 1990s.

In Australia, the disruptions have contributed to large price increases for some consumer durable items, including cars and some household goods. These developments, alongside the lift in energy prices, and pushed up annual headline consumer price inflation (CPI) to 3.0% in the September quarter. But overall, producer price inflation remains much lower than some other parts of the world, touching 2.9% in the September quarter. If producer prices lift more than consumer prices, this may squeeze the profit margins of some businesses, as it suggests rising costs have not been entirely passed onto consumers.

However, trimmed mean CPI, a measure of underlying price pressures and the Reserve Bank’s preferred measure of inflation, is still modest. In fact, it just crept up to 2.1% in the September quarter.

Pandemic curveballs

The emergence of the Omicron variant in recent weeks is a reminder that the pandemic continues to cloud the outlook with uncertainty. It also casts doubt over when supply bottlenecks will be resolved.

It is early days, and official sources are yet to confirm the transmissibility or severity of the variant. A good outcome would be that the variant is less severe than previous iterations of the virus and that current vaccines provide effective protection. This would mean governments do not need to reimpose restrictions and would allow bottlenecks to begin to ease.

On the flip side, a couple of scenarios are possible if the variant leads to poorer health outcomes and lockdowns are reintroduced. One possibility is that it exacerbates supply disruptions and prolongs higher inflation. In contrast, another possibility is that lockdowns clip demand, and, in turn inflation will recede much faster.

Central banks are watching closely

Central banks, up until recently, have been at pains to underscore these pressures are transitory. The longer supply disruptions persist, the bigger the likelihood that these ‘temporary’ price increases will become entrenched. The risk for central banks is the increase in inflation is faster and more persistent than they have forecast.

We expect inflation will pick up faster than the RBA has indicated – we forecast underlying inflation will be a little under 3% at the end of next year while the RBA expects a bit over 2%. But we also think market pricing has overshot. Investors are pinning the first rate hike on the second half of 2022. We stand by our long-held view that the first move will come in early 2023.

But no doubt there are risks to the upside for inflation. If supply bottlenecks endure, and energy prices remain elevated longer than expected, rate lift off in 2022 certainly isn’t out of the question.

The outlook for the Australian equity market is uncertain. On one hand, higher interest rates are typically perceived as a headwind for equity markets, as it becomes more expensive to borrow, and companies and consumers curb their spending. But on the other, we are at the start of an upswing in global economic growth as restrictions lift, notwithstanding any setbacks from new variants such as Omicron, which will support equity prices. Given these competing forces, and the enduring uncertainties over the pandemic, greater volatility in equity markets seems likely.

Matthew Bunny, Economist

10 December 2021

Superannuation income streams types

Calculating the rate of income support payments

This document has been created by Westpac Financial Services Limited (ABN 20 000 241 127, AFSL 233716). It provides an overview or summary only and it should not be considered a comprehensive statement on any matter or relied upon as such. This information has been prepared without taking account of your objectives, financial situation or needs. Because of this, you should, before acting on this information, consider its appropriateness, having regard to your objectives, financial situation and needs. Projections given above are predicative in character. Whilst every effort has been taken to ensure that the assumptions on which the projections are based are reasonable, the projections may be based on incorrect assumptions or may not consider known or unknown risks and uncertainties. The results ultimately achieved may differ materially from these projections. This document may contain material provided by third parties derived from sources believed to be accurate at its issue date. While such material is published with necessary permission, Westpac Financial Services Limited does not accept any responsibility for the accuracy or completeness of or endorses any such material. Except where contrary to law, Westpac Financial Services Limited intends by this notice to exclude liability for this material. Information current as at 10 December 2021. © Westpac Financial Services Limited 2021.